AS Film Studies Film Texts & Contexts Section A

Thursday 25 April 2013

Wednesday 29 August 2012

Film Style

Film styles are recognizable film techniques used by filmmakers to give specific meaning or value to their work. It can include all aspects in making a film: sound, mise-en-scene, dialogue, cinematography, or attitude.

- 1 Style and the director

- 2 Style and the audience

- 3 Difference between genre and film style

- 4 Group style

- 5 Types of film styles

- 6 References

Tuesday 28 August 2012

FILM SOUND AND MUSIC

FILM SOUND AND MUSIC

Sound, voice and music are integral to most films and/or film viewing experiences. Even the earliest silent films were often shown with live musical accompaniment. Sound enhances the imaginary world, it can provide depth, establish character and environment, introduce a new scene or cue the viewer to important information. We have organized the page according to the following categories: sound source, sound editing and film music.

film-sound-and-music

Diegetic vs. Non-Diegetic Sound

Nonsimultaneous sound

Direct Sound

Synchronous Sound

Postsynchronization Dubbing

Offscreen Sound

Sound Perspective

Sound Bridge

Voice Over

Diegetic sound is any sound that the character or characters on screen can hear. So for example the sound of one character talking to another would be diegetic. Non-diegetic sound is any sound that the audience can hear but the characters on screen cannot. Any appearance of background music is a prime example of non-diegetic sound. This clip from Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Deadsimultaneously depicts both diegetic and non-diegetic sound. The sounds of the characters speaking, the records flying, and the zombies are all diegetic; the characters can hear them. Meanwhile, the beats and riffs of the background music serves as an example of non-diegetic sound that goes unheard by Shaun, Pete, and the menacing zombies.

Nonsimultaneous Sound – Emily Johnson Nonsimultaneous sound is essentially sound that takes place earlier in the story than the current image. This type of sound can give us information about the story without us actually seeing these events taking place. In this example from Rent, Roger goes out in search of Mimi. The viewer sees him running around New York, but all they hear is earlier answering machine messages regarding previous events. The messages all describe parts of the story that have already happened, however, the viewer has not seen them happen. Direct Sound Direct sound is all of the sound that is recorded at the time of filming. In this scene from Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby, the only sounds are those that occurred when the scene was filmed. The main sound in the scene is the characters’ dialogue, but some subtle direct background noises, such as popping gum, can be heard as well. No postsynchronous sounds or music occur in the scene, which places emphasis on the characters’ dialogue and creates a more realistic, believable ambiance. Synchronous Sound Synchronous sound is sound that is matched with the action and movements being viewed. An oft-used example portrays a character playing the piano, and the viewer hears the sounds of the piano simultaneously. In this clip from The Pianist, Adrien Brody finishes up a piece in front of a German guard. Postsynchronization Dubbing Postsynchronization dubbing describes the process of adding sound to a scene after it is filmed. This sequence from Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope illustrates many different forms of postsynchronous sound. In fact, hardly any of the sound in this scene is synchronous. The space battle scenes contain laser and explosion sounds that are artificial and added to the scene after it was filmed. These sounds increase the intensity and authenticity of the scene. Later in the scene, many of the sounds inside the Rebel spaceship, including the sirens, explosions, and the droids’ voices, are all dubbed postsynchronously. The nondiegetic, postsynchronous music in the scene contributes to the suspense of the sequence. Postsynchronous sound is a staple of the Star Wars films and many other action-adventure films. Offscreen Sound Offscreen sound describes sound assumed to be in the space of a scene yet remains offscreen while the action takes place simultaneously. In this scene from The Boondock Saints the director uses offscreen sound to undermine the ideas of a detective who gives his thoughts on a recent murder. He uses this dialogue as background noise to introduce the all-star FBI agent who will be working the case Sound Perspective Sound perspective refers to the apparent distance of a sound source, evidenced by its volume, timbre, and pitch. This type of editing is most common in how the audience hears film characters’ speech. While the scene may cut from a long shot of a conversation to a medium shot of the two characters to close-up shot/ reserve-shot pairing, the soundtrack does not reproduce these relative distances and the change in volume that would naturally occur. Actors in these situations are “miked” so that the volume of their voices remains constant and audible to the audience. Sound perspective can also give us clues as to who and where is present in a scene and their relative importance to the film’s narrative. The following clip from Moulin Rouge! provides an example of the lack of sound perspective because as the camera tracks out from a medium-long to an extreme long shot of Satine, the sound quality and volume of the singer’s voice does not change as it realistically would as the viewer increases their distance from the subject. Editing devices such as this are especially important in musical films such as Moulin Rouge!, where the songs are what drive the narrative and thus maintaining the sound quality over realistic expectations becomes integral to the film. In contrast to this, below is a clip from the opening sequence of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) that shows a more realistic use of sound perspective. The sound’s distance is made obvious by the fading and increasing volume of the car’s music and people’s voices as they move toward or away from the camera. In this example sound contributes to point of view; we hear what the characters hear as they navigate the streets of a border town on foot. SOUND EDITING Sound Bridge A sound bridge is a type of sound editing that occurs when sound carries over a visual transition in a film. This type of editing provides a common transition in the continuity editing style because of the way in which it connects the mood, as suggested by the music, throughout multiple scenes. For example, music might continue through a scene change or throughout and montage sequence to tie the scenes together in a creative and thematic way. Another form of a sound bridge can help lead in or out of a scene, such as when dialogue or music occurs before or after the speaking character is scene by the audience. Voice Over A voice over is a sound device wherein one hears the voice of a character and/or narrator speaking but the character in question is not speaking those words on screen. This is often used to reveal the thoughts of a character through first person narration. Third person narration is also a common use of voice over used to provide background of characters/events or to enhance the development of the plot. As we see below in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums, a third person narrator voiced by Alec Baldwin provides background on key characters in the beginning of the film. FILM MUSIC The following sequence, from Woody Allen’s Match Point, illustrates the director’s rather unique use of character theme music. It also provides an example of the sound bridge. As Chris Wilton wanders around his new friends’ estate, he is associated with an aria from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore, sung by Enrico Caruso. The recording exposes the early sound technology used to make it, giving it an unearthly quality. Throughout the film whenever Chris ambles, he is accompanied by Caruso’s voice, perhaps signaling to his own “operatic” circumstance. The spectral quality of the recording complements the many allusions to tragic tradition in the film, including an appearance by the ghosts of Chris’s victims. In a second place, sound initiates a transition in the form of a “bridge”. Toward the end of the sequence, we begin to hear a ping pong game – it grows louder as the opera music fades until Chris enters the new scene.

Sound, voice and music are integral to most films and/or film viewing experiences. Even the earliest silent films were often shown with live musical accompaniment. Sound enhances the imaginary world, it can provide depth, establish character and environment, introduce a new scene or cue the viewer to important information. We have organized the page according to the following categories: sound source, sound editing and film music.

film-sound-and-music

Diegetic vs. Non-Diegetic Sound

Nonsimultaneous sound

Direct Sound

Synchronous Sound

Postsynchronization Dubbing

Offscreen Sound

Sound Perspective

Sound Bridge

Voice Over

SOUND SOURCE

Diegetic vs. Non-Diegetic SoundDiegetic sound is any sound that the character or characters on screen can hear. So for example the sound of one character talking to another would be diegetic. Non-diegetic sound is any sound that the audience can hear but the characters on screen cannot. Any appearance of background music is a prime example of non-diegetic sound. This clip from Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Deadsimultaneously depicts both diegetic and non-diegetic sound. The sounds of the characters speaking, the records flying, and the zombies are all diegetic; the characters can hear them. Meanwhile, the beats and riffs of the background music serves as an example of non-diegetic sound that goes unheard by Shaun, Pete, and the menacing zombies.

Nonsimultaneous Sound – Emily Johnson Nonsimultaneous sound is essentially sound that takes place earlier in the story than the current image. This type of sound can give us information about the story without us actually seeing these events taking place. In this example from Rent, Roger goes out in search of Mimi. The viewer sees him running around New York, but all they hear is earlier answering machine messages regarding previous events. The messages all describe parts of the story that have already happened, however, the viewer has not seen them happen. Direct Sound Direct sound is all of the sound that is recorded at the time of filming. In this scene from Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby, the only sounds are those that occurred when the scene was filmed. The main sound in the scene is the characters’ dialogue, but some subtle direct background noises, such as popping gum, can be heard as well. No postsynchronous sounds or music occur in the scene, which places emphasis on the characters’ dialogue and creates a more realistic, believable ambiance. Synchronous Sound Synchronous sound is sound that is matched with the action and movements being viewed. An oft-used example portrays a character playing the piano, and the viewer hears the sounds of the piano simultaneously. In this clip from The Pianist, Adrien Brody finishes up a piece in front of a German guard. Postsynchronization Dubbing Postsynchronization dubbing describes the process of adding sound to a scene after it is filmed. This sequence from Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope illustrates many different forms of postsynchronous sound. In fact, hardly any of the sound in this scene is synchronous. The space battle scenes contain laser and explosion sounds that are artificial and added to the scene after it was filmed. These sounds increase the intensity and authenticity of the scene. Later in the scene, many of the sounds inside the Rebel spaceship, including the sirens, explosions, and the droids’ voices, are all dubbed postsynchronously. The nondiegetic, postsynchronous music in the scene contributes to the suspense of the sequence. Postsynchronous sound is a staple of the Star Wars films and many other action-adventure films. Offscreen Sound Offscreen sound describes sound assumed to be in the space of a scene yet remains offscreen while the action takes place simultaneously. In this scene from The Boondock Saints the director uses offscreen sound to undermine the ideas of a detective who gives his thoughts on a recent murder. He uses this dialogue as background noise to introduce the all-star FBI agent who will be working the case Sound Perspective Sound perspective refers to the apparent distance of a sound source, evidenced by its volume, timbre, and pitch. This type of editing is most common in how the audience hears film characters’ speech. While the scene may cut from a long shot of a conversation to a medium shot of the two characters to close-up shot/ reserve-shot pairing, the soundtrack does not reproduce these relative distances and the change in volume that would naturally occur. Actors in these situations are “miked” so that the volume of their voices remains constant and audible to the audience. Sound perspective can also give us clues as to who and where is present in a scene and their relative importance to the film’s narrative. The following clip from Moulin Rouge! provides an example of the lack of sound perspective because as the camera tracks out from a medium-long to an extreme long shot of Satine, the sound quality and volume of the singer’s voice does not change as it realistically would as the viewer increases their distance from the subject. Editing devices such as this are especially important in musical films such as Moulin Rouge!, where the songs are what drive the narrative and thus maintaining the sound quality over realistic expectations becomes integral to the film. In contrast to this, below is a clip from the opening sequence of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) that shows a more realistic use of sound perspective. The sound’s distance is made obvious by the fading and increasing volume of the car’s music and people’s voices as they move toward or away from the camera. In this example sound contributes to point of view; we hear what the characters hear as they navigate the streets of a border town on foot. SOUND EDITING Sound Bridge A sound bridge is a type of sound editing that occurs when sound carries over a visual transition in a film. This type of editing provides a common transition in the continuity editing style because of the way in which it connects the mood, as suggested by the music, throughout multiple scenes. For example, music might continue through a scene change or throughout and montage sequence to tie the scenes together in a creative and thematic way. Another form of a sound bridge can help lead in or out of a scene, such as when dialogue or music occurs before or after the speaking character is scene by the audience. Voice Over A voice over is a sound device wherein one hears the voice of a character and/or narrator speaking but the character in question is not speaking those words on screen. This is often used to reveal the thoughts of a character through first person narration. Third person narration is also a common use of voice over used to provide background of characters/events or to enhance the development of the plot. As we see below in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums, a third person narrator voiced by Alec Baldwin provides background on key characters in the beginning of the film. FILM MUSIC The following sequence, from Woody Allen’s Match Point, illustrates the director’s rather unique use of character theme music. It also provides an example of the sound bridge. As Chris Wilton wanders around his new friends’ estate, he is associated with an aria from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore, sung by Enrico Caruso. The recording exposes the early sound technology used to make it, giving it an unearthly quality. Throughout the film whenever Chris ambles, he is accompanied by Caruso’s voice, perhaps signaling to his own “operatic” circumstance. The spectral quality of the recording complements the many allusions to tragic tradition in the film, including an appearance by the ghosts of Chris’s victims. In a second place, sound initiates a transition in the form of a “bridge”. Toward the end of the sequence, we begin to hear a ping pong game – it grows louder as the opera music fades until Chris enters the new scene.

EDITING

EDITING

Editing describes the relationship between shots and the process by which they are combined. It is essential to the creation of narrative space and to the establishment of narrative time. The relationship between shots may be graphic, rhythmic, spatial and/or temporal.

Filmmakers and editors may work with various goals in mind. Traditionally, commercial cinema prefers the continuity system, or the creation of a logical, continuous narrative which allows the viewer to suspend disbelief easily and comfortably. Alternatively, filmmakers may use editing to solicit our intellectual participation or to call attention to their work in a reflexive manner.

Editing

Rhythm & Pace

Spatial (shot rev. shot, 180 deg rule)

Transitions (Fades, Cross Dissolve)

Graphic

Temporal (Match on Action, Cross cutting, Parallel Editing)

Montage

Long Take

GRAPHIC RELATIONSHIPS Graphic Match (Grant Reed) Graphic matches, or match cuts, are useful in relating two otherwise disconnected scenes, or in helping to establish a relationship between two scenes. By ending one shot with a frame containing the same compositional elements (shape, color, size, etc.) as the beginning frame of the next shot, a connection is drawn between the two shots with a smooth transition. The first clip below, from Hitchcock’s Psycho, takes place just after a woman is brutally stabbed to death while in the shower. As her blood washes away down the drain with the water, the camera slowly zooms in on just the drain itself. A graphic match cut is then utilized, as the center of the drain becomes the iris of the victim’s lifeless left eye. The next clip, from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, is generally considered to be one of the most famous match cuts in all of film. As a primitive primate discovers the destructive powers of his newfound technology, the femur of a deceased animal, he tosses it high up into the air. Thousands of years pass in a single moment as a close-up of the bone cuts to a long shot of a satellite orbiting the earth, thus showing the vast technological advancements made over the past millennia. RHYTHMIC RELATIONSHIPS Rhythm (Ben Etkin) Rhythm editing describes an assembling of shots and/or sequences according to a rhythmic pattern of some kind, usually dictated by music. It can be narrative, as in the clip from Woody Allen’s Bananas below, or, a music video type collage, as in the second clip from Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. In either case, dialogue is suppressed and the musical relationship between shots takes center stage. In Allen’s Bananas, the use of a vaudeville-esque tune recalls Charlie Chaplin and early cinematic comedy. Like Chaplin’s characters, Fielding Melish’s actions and adventures continually result in humorous misadventure. In the sequence below, he heroically expels two thugs from a subway car. The length of the shots is determined by the quick tempo of the piano recording: as the villains’ abuse of innocent passengers reaches a climax, the shots become shorter and shorter. The quick editing builds suspense before the hero unpredictably rises and throws them off the train. In the next sequence, from Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, the only logic connecting the shots is that provided by Bow Wow Wow’s song, “I want candy”, and a few graphic matches. The sequence is a hallmark of Coppola’s style – interweaving period decadence and frivolity with a contemporary youthful exuberance – which is also distinctively feminine. SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS Establishing Shot (Ben Etkin) The Establishing Shot or sequence serves to situate the audience within a particular environment or setting and/ or to introduce an important character or characters. The establishing shot is usually the first or the first few shots in a sequence, and as such, it must be very efficient in portraying the context. Typically, establishing shots are Extreme Long Shots or Long Shots, followed by progressively closer framing. Quentin Tarantino introduces his film Inglorious Basterds, with an extreme long shot of the countryside, suggestive of rural France. It is followed by a medium shot of the dairy farmer, who will dominate the first scene. One of the man’s daughters is also shown, first in a medium shot and then in medium close-up, hanging clothes. Moreover, the sequence establishes the central conflict, with the arrival of the German motor cars, shown in POV shots from the perspective of the farmer and his daughter. Oliver Stone opens his film W. in the opposite manner. From an extreme close-up, a combined zoom out and pan reveals George standing in the middle of an empty ballpark. The final clip, from the conclusion of the Japanese psychological thriller, 2LDK (“2-Bedroom Apartment”), is another example of the establishing shot composed in reverse order. This sequence shows an incremental expansion of the frame (in multiple shots) to include elements beyond the dead bodies and eventually the entire city of Tokyo. Shot/ Reverse Shot Shot/Reverse Shot is an editing technique that defined as multiple shots edited together in a way that alternates characters, typically to show both sides of a conversation situation. There are multiple ways this can be accomplished, with common examples being over the shoulder shots, angled shots, left/right alternating shots, and often a combination of the three. In the first clip below, from Terry Zwigoff’s Bad Santa, we see a standard over the shoulder SRS. This, combined with eye-line matches between the two main negotiators shows how focused each is on the other. The over the shoulder technique allows the viewer to see the facial expressions of each character while listening or speaking. More importantly, the over the shoulder technique creates a sense of space between the characters greater than the actual distance between them. This keeps the frame from being uncomfortably cramped, and also shows the distance between the characters’ different standpoints. The second clip is from director John Dahl’s Rounders. There is a bit of an experimental aspect to the SRSs in the clip. As opposed to the clip above, the SRS technique is used to distort space in such a way that we observe less than there actually is. In reality there is an 8 or so foot table separating the characters: the SRS lessens this to a point where the scene seems almost intimate. We see the characters alternating left and right sides, which is a standard ploy of continuity editing. Again, eye-line matches are used to show how intensely each character is focusing on the other. Spatial Continuity: 180 Degree System Eye-line Match In an eye-line match, a shot of a character looking at something cuts to another shot showing exactly what the character sees. Essentially, the camera temporarily becomes the character’s eyes with this editing technique. In many cases, when the sequence cuts to the eye-line, camera movement is used to imply movement of the character’s eyes. For example, a pan from left to right would imply that the character is moving his/her eyes or head from left to right. Because the audience sees exactly what the character sees in an eye-line match, this technique is used to connect the audience with that character, seeing as we practically become that character for a moment. Each of the following sequences is from No Country For Old Men, directed by the Coen Brothers. In the first clip, five eye-line matches are shown in a sequence that’s only a minute long. The first of these contains movement from left to right, mocking Llewelyn’s motion as he walks up to the dead body. We then see relatively still eye-line matches as Llewelyn looks at man’s face, and then at the gun as he picks it up. The next eye-line match is shown as Llewelyn opens the briefcase of money, which contains a slight zoom. This zoom is not necessarily used to mimic Llewelyn’s eye movement, but rather his thought and emotion, as the sight of all the money understandably “brings him in.” The Coen brothers decided to use so many eye-line matches in this sequence and in the rest of Llewelyn’s journey so that the audience would come closer to experiencing what he was experiencing. In the second clip, portraying Anton’s unfortunate car ride, we see multiple eye-line matches once again. The first and last eye-line match simply follow Anton’s eyes as he looks at the road while driving. We also see another eye-line match of Anton checking his rear-view mirror; in this match you can gain an appreciation for how perfect the angle is, mimicking exactly what the character sees. With these eye-line matches, we feel almost as if we are driving the car, which makes the crash all the more disturbing. As illustrated in these two sequences, and throughout the rest of the movie, the Coen brothers wanted us to gain perspective on both Llewelyn and Anton. Through this, we gain a better understanding of the relationship between the hunter and the hunted, one of the film’s major themes. Cut-in and Cut-away This sequence, taken from Tarantino’s Sukiyaki Western Django (2007) provide an examples of the cut-in. Cut-out or away is the reverse, bringing the viewer from a close view to a more distant one. The sequence opens with an extreme long shot of the area’s landscape, a high-angled tracking shot (probably via helicopter) –giving us a wide panoramic view of the area. A cut suddenly transports the viewer somewhere within the landscape to a medium shot of character lying on the floor in his room. TEMPORAL RELATIONSHIPS Continuity editing: The Match on Action Match on Action is an editing technique used in continuity editing that cuts two alternate views of the same action together at the same moment in the move in order to make it seem uninterrupted. This allows the same action to be seen from multiple angles without breaking its continuous nature. It fills out a scene without jeopardizing the reality of the time frame of the action. In the first scene above, Peter Jackson uses matches on action to give the chase a sense of dynamism. The viewer can never assume what is going to happen next, as the scene is constantly shifting. He uses a very complex version of match on action, jumping from close ups to far away helicopter shots and back without a pause. It is almost dizzying, yet thrilling at the same time. Be sure to keep your eye on the white horse; this is the character we are following and although hard to see at times it is present in every part of the clip. The second scene is from Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky IV. Here we see a different, simpler style of matches on action. The camera stays at relatively the same level, with few zooms in or out. The matches on action are used to keep the fight realistic looking, as well as to keep a certain character in focus/the center of the screen. The final sequence gives us a Point-of-View shot from the angle of the “Genji” warrior (shown in white) to the “Heike” gunman in red as he is shot to the ground. In this sequence, we also have an example of continuity as the Heike man first falls to the ground and we cut to him closer up on the ground in the same position. This Heike warrior is first shown standing up; though he is very small, you can see him in the distance. After the Genji warrior takes aim and fires at him, you notice him drop in the background towards where the Genji warrior has his gun aimed; the match on action comes as the camera cuts to him falling down. Parallel Editing Parallel editing is a technique used to portray multiple lines of action, occurring in different places, simultaneously. In most but not all cases of this technique, these lines of action are occurring at the same time. These different sequences of events are shown simultaneously because there is usually some type of connection between them. This connection is either understood by the audience throughout the sequence, or will be revealed later on in the movie. The first clip is from No Country For Old Men directed by the Coen Brothers, and the second is from Batman: The Dark Knight directed by Christopher Nolan. In this first clip, we see parallel editing used primarily to add suspense to the situation. At first, the intervals between showing Lewelyn and Anton are relatively long, but as they shorten later on in the sequence, additional suspense is added. Just as we see in the previous clips from the film, there are many eye-line matches shown for both of the characters. This combination of parallel editing and eye-line matches for each line of action allows the viewer to practically experience both sides of the event first-hand. The second clip offers a different kind of parallel editing in the use of sound. The basement of criminals contains only diagetic sound, but as the sequence cuts to the police raid, the voice of the man on the TV carries over, becoming non-diagetic sound. This created the effect of the man practically narrating what we see occurring with the police. In this way, parallel editing can be used not only to add suspense but also to narrate a line of action with another line of action. Alternative transitions Superimposition Th following sequence is an example of superimposition. Superimposition refers to the process by which frames are overlapped, either mechanically or digitally, in order to achieve a layered transition. Japanese cinema sometimes uses traditional “kanji” calligraphy superimposed over standard film in several ways; the first of these being to illustrate a famous quotation or religious koan (a phrase chanted to bring about enlightenment), such as this example in which Tarantino says the Japanese proverb, “life is all about goodbyes” (サヨナラだけが人生だ) with the same words superimposed over the screen. Fade -in In this sequence from Sukiyaki Western Django, the calligraphic message provides an example of the fade-in. The style used in “Sukiyaki Western Django” is reminiscent of filmmakers such as Kurosawa, who used this archaic writing technique to embed a sort of traditionalism into his media. All in all, this effect has the added value of reminding us that though we are watching a Western, there is a Japanese component that underlies all the events of the film, and we cannot forget this in sight of the lush mise en scène that encompasses the entirety of the piece. ALTERNATIVES TO THE CONTINUITY SYSTEM In-Camera Editing Long Take (Grant Reed) Long takes are simply shots that extend for a long period of time before cutting to the next shot. Generally, any take greater than a minute in length is considered a long take. Usually done with a moving camera, long takes are often used to build suspense or capture the attention of audience of without breaking their concentration by cutting the film. The opening scene from Robert Zemeckis’ Forrest Gump follows a feather blowing carefree in the wind, eventually landing on the foot of the protagonist who proceeds to pick it up and place it in his suitcase. This scene acts as a metaphor for the whole movie, as the feather represents Forrest. Just as the feather blows around for what seems like forever, just going where the wind takes it until it eventually lands in a safe place, Forrest seems to just blow aimlessly through life, going wherever life and fate may take him with out too much consideration of his own, until he eventually lands in a happy place. The next long take is from Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption. A white bus is seen driving up the street towards a long building. As the bus turns to drive around the building the camera goes straight over the top of the building to reveal the vast expanses of Shawshank Prison. Hundreds of prisoners in the yard are all seen walking in the same direction, seemingly toward the same place. As the camera makes it to the end of the prison yard the bus returns to the frame, meeting a group of guards at the same spot all of the prisoners had been heading towards. This long take sequence, from Scorsese’s Mean Streets, shows Charlie (Harvey Keitel) in a state of barely coherent drunkenness. The sequence was accomplished by attaching a Steadicam to the actor’s body in such a way as to continually frame his face in close-up in spite of his uncertain movements. The position of the camera serves to capture the disorientation and estrangement of the character as he stumbles around the crowded bar. The red color of the image, together with the absurd musical accompaniment, helps to render the atmosphere of a seedy night club Jump-Cut (Nelson) A Jump-Cut is an example of the elliptical style of editing where one shot seems to be abruptly interrupted. Typically the background will change while the individuals stay the same, or vice versa. Jump-cuts stray from the more contemporary style of continuity editing where the plot flows seamlessly to a more ambiguous story line. An example of this editing style can be found in the following clips from Capote (2005). Associative Editing or “Montage” The following clip is taken from Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. This unique combination of shots shows a marble lion reacting to the sailors’ rebellion in the harbor. In the context of the story, the ship opens fire on Cossack reinforcements sent to quell its revolt. Eisenstein integrates lions sculpted in various postures to suggest that all of Moscow is awakening to the people’s cause. The sequence requires the viewer to interpret, to “read” the metaphor inherent in the statues and to derive a meaning from their presence in the diegesis. Hollywood-style Montage (Nelson) Montage also describes the approach used in commercial cinema to piece together fragments of different yet related images, sounds/music, often in the style of a music video. The following sequence, from Pretty Woman (1991), is an example of the hollywood style montage. The film, starring Richard Gere and Julia Roberts, shows the main character Vivienne as she transitions from a scantily-clad, unrefined hooker, into Edward’s elegant, poised and well-dressed companion. The soundtrack plays over the background as snippets of various clothing and body parts are shown. In the concluding frame of sequence, the final product, the “new Vivienne”, approaches the camera in a white, tailored outfit and a ladylike hat.

Editing describes the relationship between shots and the process by which they are combined. It is essential to the creation of narrative space and to the establishment of narrative time. The relationship between shots may be graphic, rhythmic, spatial and/or temporal.

Filmmakers and editors may work with various goals in mind. Traditionally, commercial cinema prefers the continuity system, or the creation of a logical, continuous narrative which allows the viewer to suspend disbelief easily and comfortably. Alternatively, filmmakers may use editing to solicit our intellectual participation or to call attention to their work in a reflexive manner.

Editing

Rhythm & Pace

Spatial (shot rev. shot, 180 deg rule)

Transitions (Fades, Cross Dissolve)

Graphic

Temporal (Match on Action, Cross cutting, Parallel Editing)

Montage

Long Take

GRAPHIC RELATIONSHIPS Graphic Match (Grant Reed) Graphic matches, or match cuts, are useful in relating two otherwise disconnected scenes, or in helping to establish a relationship between two scenes. By ending one shot with a frame containing the same compositional elements (shape, color, size, etc.) as the beginning frame of the next shot, a connection is drawn between the two shots with a smooth transition. The first clip below, from Hitchcock’s Psycho, takes place just after a woman is brutally stabbed to death while in the shower. As her blood washes away down the drain with the water, the camera slowly zooms in on just the drain itself. A graphic match cut is then utilized, as the center of the drain becomes the iris of the victim’s lifeless left eye. The next clip, from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, is generally considered to be one of the most famous match cuts in all of film. As a primitive primate discovers the destructive powers of his newfound technology, the femur of a deceased animal, he tosses it high up into the air. Thousands of years pass in a single moment as a close-up of the bone cuts to a long shot of a satellite orbiting the earth, thus showing the vast technological advancements made over the past millennia. RHYTHMIC RELATIONSHIPS Rhythm (Ben Etkin) Rhythm editing describes an assembling of shots and/or sequences according to a rhythmic pattern of some kind, usually dictated by music. It can be narrative, as in the clip from Woody Allen’s Bananas below, or, a music video type collage, as in the second clip from Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. In either case, dialogue is suppressed and the musical relationship between shots takes center stage. In Allen’s Bananas, the use of a vaudeville-esque tune recalls Charlie Chaplin and early cinematic comedy. Like Chaplin’s characters, Fielding Melish’s actions and adventures continually result in humorous misadventure. In the sequence below, he heroically expels two thugs from a subway car. The length of the shots is determined by the quick tempo of the piano recording: as the villains’ abuse of innocent passengers reaches a climax, the shots become shorter and shorter. The quick editing builds suspense before the hero unpredictably rises and throws them off the train. In the next sequence, from Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, the only logic connecting the shots is that provided by Bow Wow Wow’s song, “I want candy”, and a few graphic matches. The sequence is a hallmark of Coppola’s style – interweaving period decadence and frivolity with a contemporary youthful exuberance – which is also distinctively feminine. SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS Establishing Shot (Ben Etkin) The Establishing Shot or sequence serves to situate the audience within a particular environment or setting and/ or to introduce an important character or characters. The establishing shot is usually the first or the first few shots in a sequence, and as such, it must be very efficient in portraying the context. Typically, establishing shots are Extreme Long Shots or Long Shots, followed by progressively closer framing. Quentin Tarantino introduces his film Inglorious Basterds, with an extreme long shot of the countryside, suggestive of rural France. It is followed by a medium shot of the dairy farmer, who will dominate the first scene. One of the man’s daughters is also shown, first in a medium shot and then in medium close-up, hanging clothes. Moreover, the sequence establishes the central conflict, with the arrival of the German motor cars, shown in POV shots from the perspective of the farmer and his daughter. Oliver Stone opens his film W. in the opposite manner. From an extreme close-up, a combined zoom out and pan reveals George standing in the middle of an empty ballpark. The final clip, from the conclusion of the Japanese psychological thriller, 2LDK (“2-Bedroom Apartment”), is another example of the establishing shot composed in reverse order. This sequence shows an incremental expansion of the frame (in multiple shots) to include elements beyond the dead bodies and eventually the entire city of Tokyo. Shot/ Reverse Shot Shot/Reverse Shot is an editing technique that defined as multiple shots edited together in a way that alternates characters, typically to show both sides of a conversation situation. There are multiple ways this can be accomplished, with common examples being over the shoulder shots, angled shots, left/right alternating shots, and often a combination of the three. In the first clip below, from Terry Zwigoff’s Bad Santa, we see a standard over the shoulder SRS. This, combined with eye-line matches between the two main negotiators shows how focused each is on the other. The over the shoulder technique allows the viewer to see the facial expressions of each character while listening or speaking. More importantly, the over the shoulder technique creates a sense of space between the characters greater than the actual distance between them. This keeps the frame from being uncomfortably cramped, and also shows the distance between the characters’ different standpoints. The second clip is from director John Dahl’s Rounders. There is a bit of an experimental aspect to the SRSs in the clip. As opposed to the clip above, the SRS technique is used to distort space in such a way that we observe less than there actually is. In reality there is an 8 or so foot table separating the characters: the SRS lessens this to a point where the scene seems almost intimate. We see the characters alternating left and right sides, which is a standard ploy of continuity editing. Again, eye-line matches are used to show how intensely each character is focusing on the other. Spatial Continuity: 180 Degree System Eye-line Match In an eye-line match, a shot of a character looking at something cuts to another shot showing exactly what the character sees. Essentially, the camera temporarily becomes the character’s eyes with this editing technique. In many cases, when the sequence cuts to the eye-line, camera movement is used to imply movement of the character’s eyes. For example, a pan from left to right would imply that the character is moving his/her eyes or head from left to right. Because the audience sees exactly what the character sees in an eye-line match, this technique is used to connect the audience with that character, seeing as we practically become that character for a moment. Each of the following sequences is from No Country For Old Men, directed by the Coen Brothers. In the first clip, five eye-line matches are shown in a sequence that’s only a minute long. The first of these contains movement from left to right, mocking Llewelyn’s motion as he walks up to the dead body. We then see relatively still eye-line matches as Llewelyn looks at man’s face, and then at the gun as he picks it up. The next eye-line match is shown as Llewelyn opens the briefcase of money, which contains a slight zoom. This zoom is not necessarily used to mimic Llewelyn’s eye movement, but rather his thought and emotion, as the sight of all the money understandably “brings him in.” The Coen brothers decided to use so many eye-line matches in this sequence and in the rest of Llewelyn’s journey so that the audience would come closer to experiencing what he was experiencing. In the second clip, portraying Anton’s unfortunate car ride, we see multiple eye-line matches once again. The first and last eye-line match simply follow Anton’s eyes as he looks at the road while driving. We also see another eye-line match of Anton checking his rear-view mirror; in this match you can gain an appreciation for how perfect the angle is, mimicking exactly what the character sees. With these eye-line matches, we feel almost as if we are driving the car, which makes the crash all the more disturbing. As illustrated in these two sequences, and throughout the rest of the movie, the Coen brothers wanted us to gain perspective on both Llewelyn and Anton. Through this, we gain a better understanding of the relationship between the hunter and the hunted, one of the film’s major themes. Cut-in and Cut-away This sequence, taken from Tarantino’s Sukiyaki Western Django (2007) provide an examples of the cut-in. Cut-out or away is the reverse, bringing the viewer from a close view to a more distant one. The sequence opens with an extreme long shot of the area’s landscape, a high-angled tracking shot (probably via helicopter) –giving us a wide panoramic view of the area. A cut suddenly transports the viewer somewhere within the landscape to a medium shot of character lying on the floor in his room. TEMPORAL RELATIONSHIPS Continuity editing: The Match on Action Match on Action is an editing technique used in continuity editing that cuts two alternate views of the same action together at the same moment in the move in order to make it seem uninterrupted. This allows the same action to be seen from multiple angles without breaking its continuous nature. It fills out a scene without jeopardizing the reality of the time frame of the action. In the first scene above, Peter Jackson uses matches on action to give the chase a sense of dynamism. The viewer can never assume what is going to happen next, as the scene is constantly shifting. He uses a very complex version of match on action, jumping from close ups to far away helicopter shots and back without a pause. It is almost dizzying, yet thrilling at the same time. Be sure to keep your eye on the white horse; this is the character we are following and although hard to see at times it is present in every part of the clip. The second scene is from Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky IV. Here we see a different, simpler style of matches on action. The camera stays at relatively the same level, with few zooms in or out. The matches on action are used to keep the fight realistic looking, as well as to keep a certain character in focus/the center of the screen. The final sequence gives us a Point-of-View shot from the angle of the “Genji” warrior (shown in white) to the “Heike” gunman in red as he is shot to the ground. In this sequence, we also have an example of continuity as the Heike man first falls to the ground and we cut to him closer up on the ground in the same position. This Heike warrior is first shown standing up; though he is very small, you can see him in the distance. After the Genji warrior takes aim and fires at him, you notice him drop in the background towards where the Genji warrior has his gun aimed; the match on action comes as the camera cuts to him falling down. Parallel Editing Parallel editing is a technique used to portray multiple lines of action, occurring in different places, simultaneously. In most but not all cases of this technique, these lines of action are occurring at the same time. These different sequences of events are shown simultaneously because there is usually some type of connection between them. This connection is either understood by the audience throughout the sequence, or will be revealed later on in the movie. The first clip is from No Country For Old Men directed by the Coen Brothers, and the second is from Batman: The Dark Knight directed by Christopher Nolan. In this first clip, we see parallel editing used primarily to add suspense to the situation. At first, the intervals between showing Lewelyn and Anton are relatively long, but as they shorten later on in the sequence, additional suspense is added. Just as we see in the previous clips from the film, there are many eye-line matches shown for both of the characters. This combination of parallel editing and eye-line matches for each line of action allows the viewer to practically experience both sides of the event first-hand. The second clip offers a different kind of parallel editing in the use of sound. The basement of criminals contains only diagetic sound, but as the sequence cuts to the police raid, the voice of the man on the TV carries over, becoming non-diagetic sound. This created the effect of the man practically narrating what we see occurring with the police. In this way, parallel editing can be used not only to add suspense but also to narrate a line of action with another line of action. Alternative transitions Superimposition Th following sequence is an example of superimposition. Superimposition refers to the process by which frames are overlapped, either mechanically or digitally, in order to achieve a layered transition. Japanese cinema sometimes uses traditional “kanji” calligraphy superimposed over standard film in several ways; the first of these being to illustrate a famous quotation or religious koan (a phrase chanted to bring about enlightenment), such as this example in which Tarantino says the Japanese proverb, “life is all about goodbyes” (サヨナラだけが人生だ) with the same words superimposed over the screen. Fade -in In this sequence from Sukiyaki Western Django, the calligraphic message provides an example of the fade-in. The style used in “Sukiyaki Western Django” is reminiscent of filmmakers such as Kurosawa, who used this archaic writing technique to embed a sort of traditionalism into his media. All in all, this effect has the added value of reminding us that though we are watching a Western, there is a Japanese component that underlies all the events of the film, and we cannot forget this in sight of the lush mise en scène that encompasses the entirety of the piece. ALTERNATIVES TO THE CONTINUITY SYSTEM In-Camera Editing Long Take (Grant Reed) Long takes are simply shots that extend for a long period of time before cutting to the next shot. Generally, any take greater than a minute in length is considered a long take. Usually done with a moving camera, long takes are often used to build suspense or capture the attention of audience of without breaking their concentration by cutting the film. The opening scene from Robert Zemeckis’ Forrest Gump follows a feather blowing carefree in the wind, eventually landing on the foot of the protagonist who proceeds to pick it up and place it in his suitcase. This scene acts as a metaphor for the whole movie, as the feather represents Forrest. Just as the feather blows around for what seems like forever, just going where the wind takes it until it eventually lands in a safe place, Forrest seems to just blow aimlessly through life, going wherever life and fate may take him with out too much consideration of his own, until he eventually lands in a happy place. The next long take is from Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption. A white bus is seen driving up the street towards a long building. As the bus turns to drive around the building the camera goes straight over the top of the building to reveal the vast expanses of Shawshank Prison. Hundreds of prisoners in the yard are all seen walking in the same direction, seemingly toward the same place. As the camera makes it to the end of the prison yard the bus returns to the frame, meeting a group of guards at the same spot all of the prisoners had been heading towards. This long take sequence, from Scorsese’s Mean Streets, shows Charlie (Harvey Keitel) in a state of barely coherent drunkenness. The sequence was accomplished by attaching a Steadicam to the actor’s body in such a way as to continually frame his face in close-up in spite of his uncertain movements. The position of the camera serves to capture the disorientation and estrangement of the character as he stumbles around the crowded bar. The red color of the image, together with the absurd musical accompaniment, helps to render the atmosphere of a seedy night club Jump-Cut (Nelson) A Jump-Cut is an example of the elliptical style of editing where one shot seems to be abruptly interrupted. Typically the background will change while the individuals stay the same, or vice versa. Jump-cuts stray from the more contemporary style of continuity editing where the plot flows seamlessly to a more ambiguous story line. An example of this editing style can be found in the following clips from Capote (2005). Associative Editing or “Montage” The following clip is taken from Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. This unique combination of shots shows a marble lion reacting to the sailors’ rebellion in the harbor. In the context of the story, the ship opens fire on Cossack reinforcements sent to quell its revolt. Eisenstein integrates lions sculpted in various postures to suggest that all of Moscow is awakening to the people’s cause. The sequence requires the viewer to interpret, to “read” the metaphor inherent in the statues and to derive a meaning from their presence in the diegesis. Hollywood-style Montage (Nelson) Montage also describes the approach used in commercial cinema to piece together fragments of different yet related images, sounds/music, often in the style of a music video. The following sequence, from Pretty Woman (1991), is an example of the hollywood style montage. The film, starring Richard Gere and Julia Roberts, shows the main character Vivienne as she transitions from a scantily-clad, unrefined hooker, into Edward’s elegant, poised and well-dressed companion. The soundtrack plays over the background as snippets of various clothing and body parts are shown. In the concluding frame of sequence, the final product, the “new Vivienne”, approaches the camera in a white, tailored outfit and a ladylike hat.

Mise-en-scene

MISE-EN-SCENE

Mise en scène encompasses the most recognizable attributes of a film – the setting and the actors; it includes costumes and make-up, props, and all the other natural and artificial details that characterize the spaces filmed. The term is borrowed from a French theatrical expression, meaning roughly “put into the scene”. In other words, mise-en-scène describes the stuff in the frame and the way it is shown and arranged. We have organized this page according to four general areas: setting, lighting, costume and staging. At the end we have also included some special effects that are closely related to mise-en-scène.mise-en-scene

SETTING

(Lowe)Setting creates both a sense of place and a mood and it may also reflect a character’s emotional state of mind. It can be entirely fabricated within a studio – either as an authentic re-construction of reality or as a whimsical fiction – but it may also be found and filmed on-location. In the following image, from Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006), the ornate décor evokes 17th century France and the castle of Versailles. But here the baroque detailing overwhelms the character, conveying her despair. The actress’s position in relation to the objects within the frame suggests that, as a pawn in the dynastic enterprise, Marie Antoinette is little more than a footstool.

The next shot, from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Earth Seen From the Moon [La terra vista dalla luna, 1966], provides a good example of the many and various effects that can be achieved via mise-en-scène. Although the film was shot on-location, the director’s style is not altogether realist. While he wishes to depict a shanty town in the suburbs of Rome, the colorful rubble and freshly painted buildings underscore his playful, ironic approach to the subject matter. The vibrantly clad children have no active role in the film and, since Pasolini means to criticize romanticized visions of Italian poverty, they are to be seen as location details.

x

LIGHTING

(Manrodt)Three-Point Lighting

This arrangement of key, fill, and backlight provides even illumination of the scene and, as a result, is the most commonly used lighting scheme in typical narrative cinema. The light comes from three different directions to provide the subject with a sense of depth in the frame, but not dramatic enough to anything deeper than light shadows behind the subject.

Blake Edward’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)

applied the three-point lighting technique to illuminate scenes. Though

the subjects of the frame (Audrey Hepburn and George Peppard) are

properly highlighted, faint shadows are visible in the background,

adding to the depth of frame.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) also utilized the three-point scheme. There is enough contrast in the backlight and highlight that the people in the crowded scenes are distinguishable from one another.

High-Key Lighting

High-key lighting involves the fill lighting (used in the three-point technique at a lower level) to be increased to near the same level as the key lighting. With this even illumination, the scene appears very bright and soft, with very few shadows in the frame. This style is used most commonly in musicals and comedies, especially of the classic Hollywood age.

Sofia Coppola took a soft, high-key approach to illumination in her film Marie Antoinette (2006).

An example of the common use of high-key lighting in musicals and comedies of the classic Hollywood era is its presence in The Wizard of Oz (1939).

Low-Key Lighting

Low-key lighting is the technical opposite of the high-key arrangement, because in low-key the fill light is at a very low level, causing the frame to be cast with large shadows. This causes stark contrasts between the darker and lighter parts of the framed image, and for much of the subject of the shot to be hidden behind in the shadows. This lighting style is most effective in film noir productions and gangster films, as a very dark and mysterious atmosphere is created from this obscuring light.

One of the most noted for their use of low-key lighting in their films was Orson Welles. Used extensively throughout his film noir Touch of Evil (1958), Welles also featured low-key lighting in several scenes of Citizen Kane (1941).

COSTUME

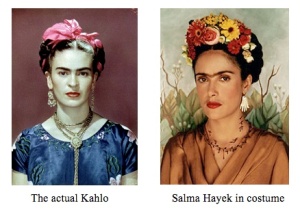

(Mertz)Arguably the most easily noticeable aspect of mise-en-scene is costume. Costume can include both makeup or wardrobe choices used to convey a character’s personality or status, and to signify these differences between characters. Costume is an important part of signifying the era in which the film is set and advertising that era’s fashions.

In biographical films, costume is an important aspect of making an actor resemble a historical character. For example, in Frida, the actress Salma Hayek was not only dressed in Mexican garb contemporaneous with the 1940’s, she is also given a fake unibrow to more closely resemble the painter Frida Kahlo.

In My Fair Lady,

changes in costume are essential in signifying the character Eliza

Doolittle‘s transformation from a ragged street urchin to polished

social queen. Before, she is dressed in rags and her face is dirty, but

after receiving etiquette training she is dressed elegantly in order to

signify her acceptance into upper class.

In My Fair Lady,

changes in costume are essential in signifying the character Eliza

Doolittle‘s transformation from a ragged street urchin to polished

social queen. Before, she is dressed in rags and her face is dirty, but

after receiving etiquette training she is dressed elegantly in order to

signify her acceptance into upper class.SPACE (Lafauci, Macfarlane)

Deep Space

A movie uses deep space when there are important components in the frame located both close to and far from the camera. It is used to emphasize the distance between objects and/or characters, as well as any obstacles that exist between them. In Finding Nemo, there is an ongoing juxtaposition between the tank in the dentist’s office and the ocean. In this image, Nemo and Gill are discussing the possibility that Nemo’s father, Marlin, might be waiting for him in the harbor, which is visible in the distance. Deep space is used in this frame to stress how far away Nemo is from his father and the barriers separating them.

Shallow Space

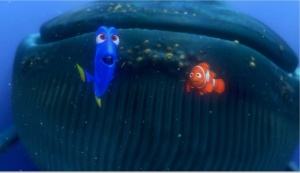

The opposite of deep space is shallow space. In shallow space, the image appears flat or two dimensional, because there is little or no depth. In this image from Finding Nemo, the whale is approaching Dory and Marlin from behind, which creates suspense for the viewer, because the fish are unaware of the whale’s presence. There is a loss of realism, but it enhances the viewing by emphasizing the close proximity of the whale to Dory and Marlin and creating concern in the viewers that they may soon be eaten. Offscreen Space Offscreen space is space in the diegesis that is not physically present in the frame. The viewer becomes aware of something outside of the frame through either a character’s response to a person, thing, or event offscreen, or offscreen sound. In this video clip from American Beauty, without seeing Ricky or his video camera, the viewer becomes aware that someone present in the room is videotaping Jane, who is onscreen. The noise from the video camera and Ricky’s response to Jane’s comments enlightens viewers as to what is going on. In using offscreen space, directors employ a more creative method of conveying information to the viewer. Frontality

Frontality is when the characters are directly facing the camera, providing viewers with the feeling that they are looking right at them. In Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the director often uses frontality as well as direct address (when the character speaks to the camera). This clip is one of many in which Ferris speaks to the audience directly. This allows him to inform the viewers of his thoughts by breaking the typical boundary between the audience and the characters onscreen.

STAGING AND ACTING

(Roberts)Acting has become one of the most important elements of modern, popular film. An actor or actresses performance can make or break a movie regardless of how engaging the story is or how well the editing was done etc… It is the actor’s duty to bring his or her character to life within the framework of the story. Their emotional input dictates how strongly the audience feels about the film. An actor must be completely aware of his or her character and be ready to portray their emotions and actions as if they were their own. The actor is the basic element of 99% of films and it is their duty to bring the movie to life in a realistic and easily understood way.

Russel Crowe as the lovable but fearsome Maximus in Gladiator (2000)

Performance Style

Two of the most common styles of performance in modern cinema are method and non-method acting (also known as naturalistic vs. stylized). The method actor’s job is to become one with the character’s mannerisms, dress, upbringing, etc. Essentially, he or she must be that character to the point where they are no longer distinguishable. Conversely, non-method or stylized acting relies on a more conspicuous approach to get the director’s point across. They will overact and hyperbolize certain characteristics in an effort to dramatize, or alternatively, to undercut for a comic effect.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KwkP7Gnp7ek

Daniel Day Lewis, in his Oscar Award-winning portrayal of oil tycoon Daniel Plainview in There Will be Blood (2009). Day Lewis perfectly exemplifies method acting as the audience truly believes that he has quote “abandoned his boy” in this powerful scene.

Non-method acting was more common in early cinema where, in the absence of sound and voice, meaning was conveyed exclusively through gesture and expression.

John Cleese from the comedy troupe Monty Python. A perfect example of non-method or stylized acting.

Blocking

The meaningful arrangement of the actors on the set is called blocking. The way in which the actors are positioned can show the dominance of one character over another, the importance of family or religion, and a myriad of other relationship possibilities.

As shown in this classic scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), blocking is used to show the supremacy of “The Godfather”, the submission of his “subjects”. His son is seen in the background, waiting for his chance to be in charge.

SPECIAL EFFECTS

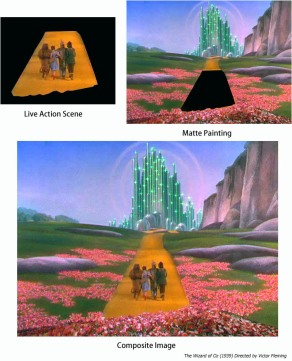

Matte ShotImage source

A matte shot is one in which two images are merged into one. This is a common process done to manipulate the scenery due to cost or impossibility. These images from The Wizard of Oz, demonstrate the process of creating a matte shot. The first is a frame from a live action shot of the group walking on the yellow brick road. The second is a painting of Emerald City and the surrounding scenery including the end of the yellow brick road. The third image combines these two components to create a matte shot, which gives the illusion that the actors are actually walking towards Emerald City, when in fact it does not even exist. It was clearly impossible in this case to build the scenery for this shot.

REAR PROJECTION (Manrodt)

Rear projection is a special effects technique used to give the illusion of filming a scene on location. The technique combines pre-filmed background footage with present foreground action. Rear projection was most popularized in driving sequences, when actors would sit inside a prop vehicle rigged up to a projector, which would cast the pre-filmed footage behind on a screen. This would give the illusion that the scene was occurring inside of a moving car, despite the fact that most instances of the rear projection technique looked quite amateur. While the foreground action would be keyed with the proper lighting and focus, the projected footage oftentimes appeared washed-out and weak.

The romantic comedy Down With Love (2003) uses a deliberately unrealistic-looking technique of rear projection to capture the look of the Doris Day-Rock Hudson movies of the early 1960s.

CINEMATOGRAPHY

CINEMATOGRAPHY

Cinematography is the act of capturing photographic images in space through the use of a number of controllable elements. These include the quality of the film stock, the manipulation of the camera lens, framing, scale and movement. Some theoreticians and film historians (Bordwell, Thompson) would also include duration, or the length of the shot, but we discuss the long take in our editing page. Cinematography is a function of the relationship between the camera lens and a light source, the focal length of the lens, the camera’s position and its capacity for motion.

cinematography link

Shot Type

Angle

Movement

Lenses/Focus

Framing

Composition

Zoom Shot The zoom shot occurs when a filmmaker changes the focal length of the lens in the middle of a shot. We appear to get closer or further away from the subject when this technique is used. In this sequence from Rob Reiner’s Stand by Me (1986), the zoom is used on the writer to emphasize his newfound inspiration for a story. FILM SPEED Rate The standard rate for a film is 24 frames per second. If more frames are added to this second the film will seem to slow down. The film will speed up if there are less than 24 frames per second. Doug Liman shoots this sequence from Swingers (1996) as a reference to Reservoir Dogs. By shooting it in 12 frames per second and then speeding it up to 24, he gives the group of guys a unique look as they leave their poker game to start their night out. FRAMING compiled by Trey Hunsucker & Daniel Hurley Image A: Orson Welles includes strange people and objects in the frame to reinforce the unsettling quality of his narrative. The blind woman has no role in the story but her presence in the foreground as Vargas telephones his wife is vaguely disturbing. Perhaps she serves as a subconscious link or an uncanny suggestion (for Mike and the spectator) that Susan is unsafe. Mike Vargas telephones his wife. Image B: Likewise, the inclusion of this sign and its message serve to increase suspense by heightening the viewer’s awareness of the possibility of evil lurking nearby. Vargas telephones his wife from a general store. Angle of Framing When filming from below or above the subject of the frame, it is known as a low or high angle. Filming from different angles is a way to show the relationship between the camera’s point of view and the subject of the frame. In this sequence from Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999), Lux wakes up the morning after homecoming lying in the middle of a football field. The high angle highlights the desolate field and her feeling of abandonment by Trip Fontaine. Level of Framing This refers to the height at which the camera is positioned in a given shot. Different camera heights are often used to display or exaggerate differences in points of view. In this scene from No Country for Old Men, as Anton Chigurh approaches his victim, the low level position of the camera creates suspense by suggesting the perspective of an unsuspecting character on the ground. Canted Framing Canted framing is where the camera is not level but tilted. It is used in action films and other films with lots of movement. It may suggest danger or disorder. In The Borne Identity, canted framing is used just for this purpose; as the official moves toward Borne, the titled frame signifies the start of an action sequence. Following Shot/Reframing A following shot is a shot that follows a character with pans, tilts, and tracking. It is unobtrusive and focuses all of the viewer’s attention on the character. In The Godfather, the camera follows Fredo as he breaks up a party. As the camera follows him, we see his growing frustration with his brother and the slow-moving partygoers. Point of View Shot A point of view shot places the camera where the viewer would imagine a characters gaze to be. This is a technique of continuity editing, because it allows us to see what the character sees without being obtrusive. In No Country for Old Men, we see a trail of blood from what seems like Anton Chigurh’s perspective. This gives the audience information about how Anton determines the whereabouts of his enemy. Wide-Angle Lens Wide-angle lenses distort the edges of a frame to emphasize the amount of space in a shot. They are used in enclosed areas where space is limited. In Signs, a wide-angle lens is used for the extreme close-up of Graham Hess before a flashback of his wife’s death. SCALE compiled by Charles Lennon Extreme Long Shot An extreme long shot is when the scale of what is being seen is tiny. In this sequence from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), the extreme long shot is being used as an establishing shot as Gandalf (Ian McKellen) enters the Shire. It was most likely shot from a crane or a helicopter, and it shows the viewer much of the fantasy world that is Middle Earth. Long Shot A long shot is when the scale of what is being seen is small. In this sequence from Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008), Sergeant Thompson (Guy Pearce) takes up most of the screen when upright, and then less when he is knocked down due to the explosion. The entire background is dust and debris from the bomb that detonated, and the scale of the long shot gives the viewer the image that Thompson was very close to the point of detonation. This is important to see because the explosion ends up killing him. Medium Long Shot A medium long shot is when what is being viewed takes up almost the entire height of the screen. In this sequence from Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1967), Blondie (Clint Eastwood) is seen staring down Tuco (Eli Wallach), and Sentenza (Lee Van Cleef) right before they duel. Blondie’s gun is visible which is important for the viewers to see for a duel sequence. This is why the medium long shot was used for most westerns. Medium Close-Up A medium close-up is when what is being viewed is large and takes up most of the screen. In this sequence from Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Red (Morgan Freeman) is seen from the chest up sitting in front of the parole board. He is fed up with the process of parole and is making a long speech about the penal system while he is just about the only object in view on the screen. Close-Up A close-up is when what is being viewed is quite large and takes up the entire screen, such as a person’s head. In this sequence from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1972), the face of Alex (Malcolm McDowell) is practically all that can be seen on the screen. He has an evil smirk on his face as he sits in the milk bar while the eery music of the opening credits still plays. The close-up is the perfect way to introduce Alex because by simply looking into his face, the viewer can see just how terrible he is. Extreme Close-Up An extreme close-up is when what is being viewed is very large, usually this is a part of someone’s face. In this sequence from Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York (2002), the camera shoots an extreme close-up of Bill the Butcher’s (Daniel Day-Lewis) left eye. It is made of glass and the pupil is in the shape of an eagle. Bill has this eye because he considers himself a patriot and a native to America, unlike the Irish immigrants who he is about to fight in the battle of the Five Points. MOVEMENT compiled by Ryan Smith Crane Shot A crane shot is achieved by mounting a camera on some type of crane device. The weight of the camera is countered by free weights at one end where the camera-man (or sometimes a remote control) can control the movement of the shot. Crane shots are often of practical use to the the filmmaker when a scene demands a shot that a normal camera person cannot take, as seen in the photo below. Above is an example of a crane in use by a filmmaker. A filmmaker using a crane to get the desired shot. The crane enables the filmmaker to move the camera through the air in virtually any direction. Crane shots are often long takes with anywhere from medium to extreme long framing. In the selected clip below, the use of a crane shot with medium framing in David Dobkin’s Wedding Crashers (2005) allows the audience to feel as if they are floating above Jeremy Grey (Vince Vaughn) and Gloria Cleary (Isla Fisher) descend down the steps in the Cleary family foyer. Towards the end of the shot, the filmmaker is able to incorporate a third character, Christopher Walken that previously existed in offscreen space. SteadiCam Shot Steadicam shots are used by filmmakers, commonly, for motion tracking shots. A steadicam device is essentially a harness that uses the camera person’s body as the support device for the camera. Steadicam was a novel way to shot a scene as it isolates the movement of the camera person from the camera. Stabilizing mechanisms counter the movements of the camera person to eliminate the inevitable imperfections present in handheld shooting (i.e. shaking). A filmmaker uses a steadicam at a sporting event. A filmmaker can adjust the amount to which the camera person’s movement is isolated from the camera. In the following clip from I Am Legend (2007), Francis Lawrence uses an imperfect steadicam shot for the majority of the sequence. The use of steadicam, here, is to heighten the audience’s feeling of Robert Neville’s (Will Smith) surprise when one of the mannequins he has set up around a post-apocalyptic Manhattan has moved. Pan A pan shot is a camera movement which follows the action, or reveals previously unframed space, as it moves horizontally. Pans occur in varying speeds for dramatic purposes. Although the most basic concept of a panning shot adheres to the movement below, a pan can also incorporate zooms, tracking of action shots and/or movement of the camera base itself. The motion of the camera during a panning shot. In the following climactic clip from Miles Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), a tracking pan follows the action of Chief (Will Sampson) as he breaks free from the mental institution that imprisons him. As the camera moves from right to left the frame changes from showing the dark mental institution to facing out a window where the sunlight (resembling a new day of freedom) is just breaking on the horizon. Tilt A tilt shot is essentially a vertical pan, where the camera moves up and down rather than from one side to another. Tilt shots often heighten an audience’s level of suspense as they are unaware what the shot will uncover. Tilt shots, like pans, serve to reveal some previously unseen space to the viewer. These shots may include zooms, tracking of action shots and/or movement of the camera base itself. In the following clip from David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999), a tilt shot is used to reveal Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) to the audience. Simultaneously, the tilting shot connotes that Durden is in control of the situation (literally above Marla Singer, as depicted by Helena Bonham Carter). If Durden does not keep Singer awake, she will succumb to the drugs she may have overdosed Tracking Shot A tracking shot follows action through space in a variety of directions. As the action, or character, moves along the screen the tracking shot enables the audience to feel as if they are moving with the action through space. This sensation is achieved by mounting the camera on a track, dolly, or moving vehicle to smoothly follow the action along a choreographed course. Recently, steadicam shots (see above) have made it possible for filmmakers to track more spontaneous action. Tracking shots were originally called Cabiria shots after they were first used by Giovanni Pastrone in Cabiria (1914). A camera is mounted on a track used by a filmmaker to follow the action through space. In the following clip from Old School (2003), directed by Todd Phillips, a tracking shot is achieved by placing the camera in the passenger seat of a moving vehicle. This particular tracking shot follows an inebriated and nude Frank Ricard (Will Ferrell) as he goes streaking. Whip Pan A whip pan follows all the same rules as a normal pan. However, a whip pan involves a quicker movement that may momentarily blur the images onscreen. Whip pans are often abrupt and imply a rapid unfolding events (i.e. action movies). The following whip pan from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) doubles as a point of view shot. In this clip, Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) quickly adjusts the focus of his attention from a roadside distraction back to the street ahead of him.

Cinematography is the act of capturing photographic images in space through the use of a number of controllable elements. These include the quality of the film stock, the manipulation of the camera lens, framing, scale and movement. Some theoreticians and film historians (Bordwell, Thompson) would also include duration, or the length of the shot, but we discuss the long take in our editing page. Cinematography is a function of the relationship between the camera lens and a light source, the focal length of the lens, the camera’s position and its capacity for motion.

cinematography link

Shot Type

Angle

Movement

Lenses/Focus

Framing

Composition

THE CAMERA LENS

compiled by Alexander Bewkes & Trey HunsuckerDeep Focus

Depth of field is the measure that can be applied to the area in focus within the frame. Deep focus, which requires a small aperture and lots of light, means that the foreground, middleground and background of the frame remain in focus. In the image below, from Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941), the extended depth of field gives the frame a 3-dimensional quality, showing multiple planes of action at once. It also allows the filmmaker to demonstrate the largesse of Kane’s dinner party and his personality. The ability to achieve deep focus was the result of a technological development in the lens in the late 193os and its adoption as a discursive mode is largely attributed to Welles.

Shallow Focus